Thanks,

Tom

The Cumulative Impacts of Transportation Projects

On Cultural Resources:

What Are They and How Can We Assess Them?

Paper presented at the Summer 2006 meeting of the

Archaeological and Historic Preservation in Transportation (ADC50) CommitteeTransportation Research Board of the National Academies July 23-26, 2006Williamsburg, Virginia

Thomas F. King

SWCA Environmental Consultants

What are cumulative impacts?

The regulations of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), governing implementation of the procedural provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act, direct agencies preparing environmental assessments to consider whether the action they’re reviewing is related to other actions with … cumulatively significant impact. (40 CFR 1508.27(b)(7)).

The regulations of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, governing implementation of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, say that adverse effects on historic properties may include reasonably foreseeable effects…that may occur later in time, be farther removed in distance, or be cumulative (36 CFR 800.5(a)(1)).

What does this “cumulative impacts” stuff mean? And how does whatever it means relate to the historic places that most of us in this conference trouble ourselves about most of the time?

CEQ’s regulations define the term as:

…the impact on the environment which results from the incremental impact of the action (being reviewed) when added to other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions regardless of what agency (Federal or non-Federal) or person undertakes such other actions.

They go on to note that:

Cumulative impacts can result from individually minor but collectively significant actions taking place over a period of time (40 CFR 1508.7)

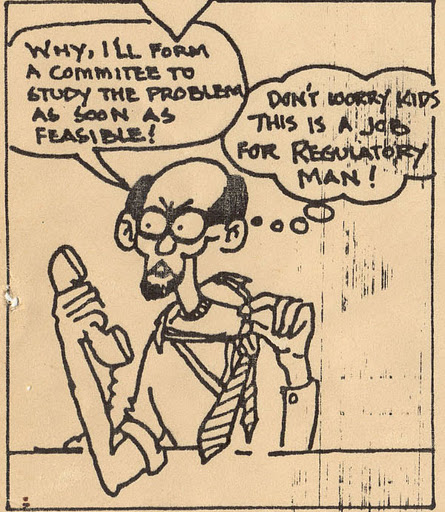

But how minor is “minor?” And how long a “period of time” should we deal with? Neither CEQ nor ACHP is very helpful; CEQ’s guidance is a mass of circumlocutions and the ACHP’s is nonexistent. We’re pretty much on our own.

I’ve recently been involved in a transportation case here in Virginia that has given me some notion of how to address cumulative impacts on historic places in Section 106 review. I’d like to take this opportunity to share what I’ve learned.

The Broad Run Bridge and US 15/29

U.S. Routes 15 and 29 come together just northeast of Broad Run in Prince William County, Virginia, and continue together southwest across the stream and through the village of Buckland. The road crosses Broad Run on a pair of bridges built in 1953 and 1980, near but not on the site of an 1807 stone bridge rebuilt in 1823 by Claudius Crozet, Napoleon Bonaparte’s bridge engineer. The road today is four lanes wide, but back in the 1950s the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) acquired right-of-way from Broad Run on to the southwest sufficient to allow widening the road to six or more lanes. A plan developed by the Northern Virginia Transportation Coordinating Council[1] and adopted by the Prince William County Board of Supervisors in 1999 -- the Northern Virginia 2020 Plan[2] – proposes expansion to six lanes by 2020.

The relationship between highways and suburban sprawl is pretty well established, and is nowhere better exemplified than in Northern Virginia. In simplest terms it’s a matter of “build it (the highway) and they (shopping malls, residential tracts) will come.” In reality the relationship is somewhat more complex and less linear – a swirl of positive feedback loops in which development begets highways which beget more development. At present in Prince William County, sprawl is chewing up the countryside on the northeast side of Broad Run. To consume the Buckland area, it needs more traffic lanes across the stream and on to the southwest.

More traffic lanes, that is, through Buckland, a remarkably well-preserved 18th-19th century mill village and its associated cultural landscape, where a group of dedicated property owners are putting together a plan to preserve the town and make it a center for historical studies and education. And through the Buckland Mills Battlefield, a relatively intact Civil War landscape where J.E.B. Stuart sent George Armstrong Custer fleeing in a battle sometimes called “Custer’s First Stand,” though Custer didn’t stand long.

The project currently under Section 106 review is the replacement of the deck on the 1953 bridge, which carries southbound traffic across Broad Run. The bridge is old and deficient, and there’s no argument over whether it needs fixing. It does. The controversy is over how to fix it.

VDOT originally proposed to replace the existing 33-foot wide bridge deck with a new one some 56 feet wide[3]. This near-doubling of the bridge’s width was handled as a categorical exclusion under NEPA and a Nationwide Permit under the Corps of Engineers’ Clean Water Act regulations, but it ran into major local opposition.

The Buckland Preservation Society, an organization of local property owners, is anxious to avoid letting their town be swallowed by sprawl. They have garnered support for a bypass around Buckland, which could allow the existing Rt. 15/29 to be reduced to a historically appropriate scale and permit the residents to implement a program of adaptive use and restoration that they hope would make Buckland into a center for the study and public appreciation of Virginia history and historic preservation. In their eyes, widening the Broad Run Bridge is a step in absolutely the wrong direction – toward implementing the Northern Virginia 2020 Plan and effectively giving their community to the developers. The Preservation Society has been joined in its opposition to the project by the American Battlefield Preservation Program of the National Park Service and by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which has included Buckland in the “Journey Through Hallowed Ground,” a Trust-coordinated program to preserve and raise public awareness of the surviving historic resources along the Old Carolina Road between Gettysburg, PA and Monticello, VA[4].

In Section 106 terms, the immediate question has been whether the bridge reconstruction would or would not have adverse effects on Buckland and the battlefield. VDOT and FHWA have said no; the Preservation Society and its allies say yes. There are some other issues involved, but at the core of the argument are cumulative impacts.

The Buckland Preservation Society says the project is part and parcel of the Northern Virginia 2020 Plan. VDOT and FHWA say no, it’s a standalone bridge repair. The Virginia SHPO and Advisory Council on Historic Preservation have been unwilling to concur in FHWA’s “no adverse effect” determination, largely because of doubts about cumulative impacts.

What I’ve learned 1: discerning cumulative impacts

Honorable people can disagree about how to regard the bridge project, and I don’t intend to rehash the arguments we’ve been having. What I do want to discuss is what immersion in this case has taught me about analyzing cumulative impacts.

The main thing it has taught me is that with respect to soft and squishy environmental variables like historic preservation, cumulative impacts analysis may not be so complicated after all. I think that perhaps – quite likely, in fact – we confuse ourselves by worrying about things like how far into the past and future we have to look in order to characterize cumulative impacts. What we have to do, I think, is simply look for patterns.

Are there general patterns of change in the human environment (under NEPA), in the environment relevant to historic properties (under Section 106)? If so, how does the project under review relate to them?

That there is a pattern of suburban sprawl in Northern Virginia is a no-brainer. That highways contribute to sprawl is obvious. That the existing highway through Buckland and the battlefield has had adverse effects in the past is indisputable – it has resulted in demolition of contributing buildings and a whole lot of cars and trucks barreling through the landscape. That it is currently having impacts is plain to see if you drive the highway, and particularly if you try to turn on or off it, or cross it. That the Northern Virginia 2020 Plan provides for a wider highway along Rt. 15/29 is literally written down in black and white (and color). Widening the existing highway, letting more cars and trucks roar through, to service more houses and businesses, cannot help but have future adverse effects on Buckland and the battlefield. There is, in other words, a clear pattern of accumulating – that is, cumulative – adverse effects, beginning in the past and extending into the not-too-distant future. The extent to which the Broad Run Bridge reconstruction contributes to this pattern can certainly be debated. To me it seems, at the very least, to do nothing to undo the pattern, reverse the trend, and as we used to say back in the days of my misspent youth, if you’re not part of the solution you’re part of the problem. Some members of the Buckland Preservation Society see a more direct and contributive relationship – that the expanded deck could itself accommodate increased traffic, or be an incremental step toward the Northern Virginia 2020 six-lane configuration. Be this as it may, I think the pattern of cumulative impacts is clear. Our business is to analyze the bridge project’s contribution (if any) to that pattern. That I think, is really all that cumulative impacts analysis is about: define the patterns and consider whether and how our project relates to them. Sometimes this may require quantitative hair-splitting about how far into the past and future to carry our analysis, but quite often, I suspect, it does not.

What I’ve learned 2: avoiding discernment

The other thing I’ve learned is how easy it is to miss the forest of cumulative impact patterning while bumping into the trees that sprout from assumptions about standard criteria and methods. At various times during consultation on the effects of the Broad Run Bridge, my clients and I have run into the following contentions – all presented by authoritative participants in the consultation as FHWA policy, official guidance, well-established good practice, or logic. We have been told that FHWA and VDOT need not or even cannot consider cumulative impacts because:

This is a maintenance project.

So if the National Park Service used jackhammers to maintain the faces on Mount Rushmore, it wouldn’t need to consider the cumulative impacts of doing so? There’s nothing in the NEPA or Section 106 regulations that exempts maintenance projects.

This kind of project is categorically excluded from review under NEPA.

This is simply a variant on the “maintenance project” theme. Under the NEPA regulations categorically excluded projects are supposed to be checked to make sure there are no “extraordinary circumstances” requiring further review, and if they are, they’re to get it. The fact that bridge reconstructions in general are categorically excluded doesn’t mean that this particular bridge reconstruction should be. And the fact that something is categorically excluded under NEPA doesn’t mean it’s categorically excluded from Section 106 review.

The project has independent utility and logical termini.

So would, say, a new twelve-lane highway up the Shenandoah Valley; would this mean we wouldn’t need to consider its contributions to cumulative impact on the valley? Independent utility and logical termini indicate that a project isn’t merely a segment of something bigger; they have nothing to do with whether the project contributes to cumulative impacts.

The purpose of and need for the project are public safety.

Yes, and? Purpose and need are things that an alternative must address in order to be viable; they don’t excuse an agency from doing any particular kind of impact analysis. Everyone wants the public to be safe, but NEPA and Section 106 suggest that we ought to try to make it so without destroying the environment. We can’t meet that requirement if we don’t analyze impacts.

The Northern Virginia 2020 Plan isn’t VDOT’s or FHWA’s plan, so we don’t need to (or can’t) consider it.

Nice try, but cumulative impacts are typically not all the products of the same change agent. Their multiple sources over time are among the things that makes them “cumulative.” Recall that the NEPA regulations direct us to consider past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions regardless of what agency (Federal or non-Federal) or person undertakes such other actions.

We don’t analyze speculative impacts, and a project is speculative until it’s funded. Widening U.S. 15/29 hasn’t been funded, so it doesn’t need to (or can’t) be considered as part of cumulative effects analysis.

This reminds me of an excuse I’ve tried with my wife from time to time. “Well, dear, I waited till now to tell you about next week’s business trip because I didn’t buy my ticket until today.” No, that really doesn’t fly. Waiting to consider the effects of a project until it’s funded not only would make cumulative impacts analysis impossible, it would stand the whole NEPA process on its head.

There’s no necessary link between widening Rts 15/29 and sprawl.

No, it’s certainly possible that a widened 15/29 will be used exclusively by tourists heading south for Charlottesville or the Blue Ridge, or by shoppers at boutiques that Buckland residents will put in along the roadside. It’s also possible that it will be used to guide flying pigs north to Capitol Hill porkbarrels. In a state whose recent gubernatorial contest turned substantially on issues of sprawl and transportation, it should be hard to keep a straight face while laying THAT proposition on the table.

Cumulative effect is the product of adding the direct and indirect effects of a project to the effects of all other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions. Reconstructing the bridge deck has no measurable impact itself, so there can be no contribution to cumulative effect.

This argument at least doesn’t fail the laugh test, but I still think it’s wrong. Whether reconstructing the bridge could have direct effects by allowing increased traffic flow through Buckland and the Battlefield is debatable, but setting that debate aside, let’s assume for a moment that it will not, cannot allow any measurable increase in traffic flow. Does the project therefore make no contribution to cumulative effect?

First consider the word “measurable.” Does an effect have to be measurable, in quantitative terms, in order to be significant? I suspect that many in the transportation planning business would say “of course,” and I sympathize. How can something be real if you can’t measure it? But many things can’t be measured, at least in quantitative terms, and the ambience of a historic community or a cultural landscape is surely one of them. Most examples of cumulative impact analysis provided in books and agency guidelines deal with things like air and water quality: past actions have put X ppm of gunk into a medium; current actions are pumping in Y ppm, future projects by others are likely to contribute Z ppm, and this project will put in or take away N ppm, so the cumulative effect is X+Y+Z+/-N. We just can’t generate that kind of equation with historic properties and other cultural resources, but that doesn’t mean they’re not parts of the environment, or not subject to impacts, cumulative or otherwise.

But cars and trucks are measurable, countable, and if the reconstructed bridge won’t allow any more of them to rumble through Buckland than rumble through it now, doesn’t that mean it doesn’t contribute to cumulative impacts?

I’d say no, it doesn’t mean that. I come back to my old saw about being part of the problem or part of the solution. The traffic situation in Buckland right now is a very damaging one from the standpoint of those who value the village and the battlefield – there are just too many vehicles, moving too fast, and some percentage of those driving them would be willing to tolerate a bottleneck along their commuting route for a few years until somebody widens that damn bridge, and hence will buy homes or frequent businesses in or beyond Buckland and hence will contribute to sprawl. Maintaining the status quo is an adverse effect on Buckland and the battlefield, and keeping the bridge for another ten or twenty years, even at its present width, maintains that status quo.

I’m not saying the bridge should not be reconstructed, that we should let if fall down with a school bus or two on it. I’m simply saying that keeping it as it is contributes to the ongoing cumulative adverse effect of the highway on the historic properties. Building a bypass, or in some other way reducing the need for people to drive through Buckland, while reducing the two-bridges across Broad Run to one and the highway to one lane each way, would contribute to solving the problem. Keeping the bridge as is does not. There’s a continuing cumulative adverse effect, and we ought to consider it under NEPA and Section 106.

Conclusion

So to summarize, I’ve learned four big things from the case of the Broad Run Bridge:

Cumulative impacts are not necessarily hard to come to grips with; they are sometimes – perhaps often – portrayed in documents as readily available as the Northern Virginia 2020 Plan.

We make it hard to grapple with cumulative impacts by insisting that they be quantifiable, and by trying to establish standard rules for what will and will not be considered.

People believe in a number of rules about cumulative impacts analysis – mostly rules that let them not conduct such analyses – that upon examination make no sense.

Even a project that itself contributes nothing new to the accumulation of impacts can still be part of a cumulative impact pattern, which should be considered when making planning decisions.

And the approach I’d advocate to cumulative impacts analysis is a very simple one, which also has four parts:

Look for patterns in what’s happening to the area;

Figure out whether and how the project we’re examining relates to these patterns;

Decide whether the relationship is positive or negative, or both; and

Consider ways to accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative.

In working on that last part of the analysis – which really goes beyond analysis, into the stuff of impact mitigation – we need to think outside our usual box, in which mitigation measures are usually quite specific – excavate this, record that, avoid this other thing – and related to quite specifically defined impacts. In the Buckland case, for example, if we can agree that the general pattern of transportation-supported sprawl is a negative one in the environment under consideration, we can consider ways to reduce sprawl’s severity or even to keep it from happening – but the methods we find will not be obviously related in some linear fashion to any specific project we’re likely to review under Section 106. They’re going to be things like pursuing the bypass around Buckland, perhaps promoting new incentives for property owners to donate conservation easements, and seeking ways to undo VDOT’s half-century old acquisition of land for highway expansion through Buckland. Some of these mitigation vehicles are going to be things that FHWA and VDOT can’t do by themselves, or do at all; we’re going to have to bring in other agencies, local governments, members of the State legislature and the Congress. We’re going to have to actually do something “holistic” about land use planning and historic preservation, rather than just talking about it.

If we can’t stretch our imaginations sufficiently to do this sort of thing, there’s not much use talking about the cumulative effects of transportation decisions on phenomena like sprawl in places like Northern Virginia. Our analyses will serve no purpose, and our talk will be nothing but hot air.

Notes:

[1] A consortium of Northern Virginia counties and cities. See www.virginiadot.org/projects/nova/nv2020/overview.htm

[2] See www.virginiadot.org/projects/nova/nv2020/

[3] During consultation, the width was reduced to 48 feet and most recently to 36 feet….(revise based on next steps in consultation).

[4] See http://www.hallowedground.org/who-we-are/partner-organizations.html