I understand that so far I’ve under 100 signatures on my petition to President Obama about reforming environmental impact assessment. Not surprising, I suppose, since it’s a fairly esoteric topic and many of those interested in it are also self-interested in maintaining the status quo. I’ve given the effort till March 1, at which point I’ll decide whether to deliver it or forget it.

So please, if you’re inclined to sign it, do so, and please distribute it to others who may do so. Here again is the text of the petition and the URL where it can be signed.

"Please seek amendments to the National Environmental Policy Act, or issue an Executive Order, to require honest, objective impact assessment that respectfully involves and is responsive to the public, and that happens BEFORE decisions are made to promote projects."

Sign at: http://signon.org/sign/president-obama-reform?source=c.fwd&r_by=408029

One gratifying thing is that a number of Indian tribes and tribal members are signing it, even though it’s not explicitly worded to address tribal concerns. I think tribes recognize that rotten, self-serving EIA is causing unnecessary destruction of environments important to them, and short-circuiting the respectful consultation the President Obama and Secretary Salazar keep promising. I hope more tribes and tribal members will sign on, and I very much hope others will, too. Wasting time and money on EIA that just whitewashes proposed projects, fails to consider feasible alternatives, and shuts the public out of decision-making serves no one. In the long run it doesn't help even those who do whitewash EIA, because it erodes the value of such work to the public, and thus undercuts support for even bothering to do it.

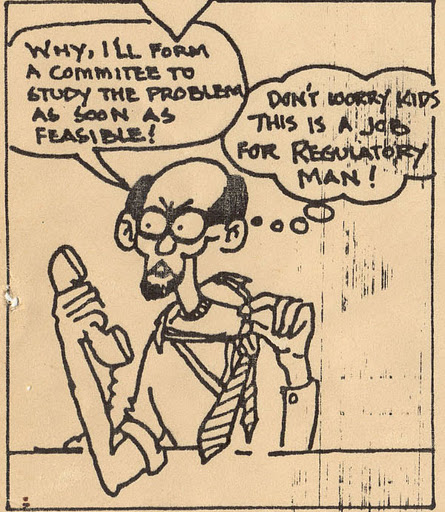

I’ve heard from a few in the EIA community who think I’m nuts for tilting at this windmill, and some who think I should instead be working quietly behind the scenes to help the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) improve things from the inside. I’m all for working quietly behind the scenes, and believe it or not have done so fairly effectively from time to time. But I’ve seen no evidence that CEQ or anyone else in this administration is interested in getting help, or for that matter that they even recognize the existence of the problem. Yet the problem seems so obvious; here’s a reminder:

1. Project proponents prevail upon the political system to support particular projects or programs with little or no consideration for their potential environmental impacts.

2. The proponents are then tasked with finding out what those impacts will be, and reporting them to agencies that often have been (or think they’ve been) given their marching orders to “streamline” review.

3. The proponents hire (and hence can fire) the EIA firms that do the studies.

4. The EIA firms give their clients good report cards (how could they do otherwise?), and carefully avoid considering alternatives to the projects they review.

5. The public, and such very interested parties as Indian tribes, are effectively shut out of the process; there may be public hearings and opportunities to review draft reports, but not to influence decision making through serious, good-faith negotiation. Even with tribes – with whom agencies are required by multiple laws to consult – “consultation” is often only a pro-forma matter that wastes time and patience, accomplishing nothing but to wear people down until they acquiesce in disgust.

What should be done? Well, the following is from a letter I sent on December 18 of last year to the president’s senior policy advisor on Native American Affairs and to the Chair of CEQ. Having outlined the problem, and illustrated it with a specific case, I suggested that action be taken to reform the administration’s approach to EIA and tribal consultation, saying:

“Such an approach might have the following elements:

1. Honestly establish what the environmental impacts of proposed actions – including but not limited to “green” projects – are likely to be before supporting and promoting them, and before telling the federal establishment to fast-track their implementation;

2. In the course of such impact assessment, honestly consider a reasonable range of alternative ways to achieve the public purposes of such actions;

3. Do not allow agencies to rely on data on and analyses of impacts and alternatives prepared by project proponents unless they have been thoroughly vetted to eliminate bias;

4. Actually consult with tribes, as well as with other stakeholders, about whether and how to proceed with projects, which alternatives to pursue, and how to mitigate adverse effects; and

5. Don’t lie.”

Yes, that seems pretty simple. Unsurprisingly, my letter has gone unanswered.

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Wednesday, January 25, 2012

Sign My Petition?

OK, it’s a windmill-tilt if ever there was one, and a mark of my growing frustration, but there it is: I’ve started a petition drive. It’s aimed at President Obama, and it says:

"Please seek amendments to the National Environmental Policy Act, or issue an Executive Order, to require honest, objective impact assessment that respectfully involves and is responsive to the public, and that happens BEFORE decisions are made to promote projects."

Pretty simple, pretty obvious, but something has to be done. Since I published my book about it in 2009 (Our Unprotected Heritage: http://www.lcoastpress.com/book.php?id=219), the situation has if anything gotten worse. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is simply understood to be, and generally accepted as, a whitewash of a project’s environmental impacts, by specialists who view themselves as (and indeed are) members of a project proponent’s planning team. This has two obnoxious effects:

1. It allows environmental impacts of all kinds – notably in my experience those on people, communities, and their cultural values – to be ignored, and

2. It undercuts public support for the conduct of impact assessment; if it’s crooked, what good is it?

The situation is especially odious where “green” projects like wind energy and solar power are involved. Since so many environmentalists have gotten on the bandwagon for such project, there’s almost no one to ride herd on their impacts and try to keep them under control. So agencies like the Bureau of Land Management are cutting corners and signing off on environmental assessments and impact statements whose pro-project biases couldn’t be clearer if they were emblazoned in neon on illuminated billboards, and utterly ignoring those Indian tribes and others who have the guts to object.

Will you sign my petition? Click here to add your name:

http://signon.org/sign/president-obama-reform?source=c.fwd&r_by=408029

"Please seek amendments to the National Environmental Policy Act, or issue an Executive Order, to require honest, objective impact assessment that respectfully involves and is responsive to the public, and that happens BEFORE decisions are made to promote projects."

Pretty simple, pretty obvious, but something has to be done. Since I published my book about it in 2009 (Our Unprotected Heritage: http://www.lcoastpress.com/book.php?id=219), the situation has if anything gotten worse. Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is simply understood to be, and generally accepted as, a whitewash of a project’s environmental impacts, by specialists who view themselves as (and indeed are) members of a project proponent’s planning team. This has two obnoxious effects:

1. It allows environmental impacts of all kinds – notably in my experience those on people, communities, and their cultural values – to be ignored, and

2. It undercuts public support for the conduct of impact assessment; if it’s crooked, what good is it?

The situation is especially odious where “green” projects like wind energy and solar power are involved. Since so many environmentalists have gotten on the bandwagon for such project, there’s almost no one to ride herd on their impacts and try to keep them under control. So agencies like the Bureau of Land Management are cutting corners and signing off on environmental assessments and impact statements whose pro-project biases couldn’t be clearer if they were emblazoned in neon on illuminated billboards, and utterly ignoring those Indian tribes and others who have the guts to object.

Will you sign my petition? Click here to add your name:

http://signon.org/sign/president-obama-reform?source=c.fwd&r_by=408029

Thursday, January 19, 2012

Two Years of Studies!

I was browsing a shop at O’Hare Airport today, and the shop’s TV was blaring.

“They’ve had TWO YEARS to study the impacts of that pipeline!” some talking head (Rick Perry, I think; I couldn’t see the screen) was saying with disgust. “That’s ENOUGH! It’s time to APPROVE IT!”

I assume the subject was the Keystone XL Pipeline. The thought that ran through my head was: “does it never occur to this doofus that one might study something for two years and conclude that it was a bad idea?”

Of course I know that it would not – particularly if the doofus was Perry, but quite likely if it was almost any other American citizen. We’ve become used to the idea that studies – particularly things like environmental impact assessments – aren’t really supposed to TEACH us anything or provide a basis for making informed decisions; they’re just things that have to be gone through, part of the price of doing business, on the way to doing what we’ve already decided to do. Sometimes, of course, we don’t bother to do studies at all (case in point: invading Iraq without thinking about what to do afterwards). Other times we waive planning studies or attenuate them into near-nonexistence (case in point: Deepwater Horizon). But even when we do them we don’t take them seriously, and don’t entertain the idea that they might lead us to re-think our initial prejudices.

Unfortunately, it’s not just the Rick Perrys of the world who think and act this way. The Obama administration has been – and continues to be – just as big a bunch of doofuses (doofi?) when it comes to its own pet projects, be they renewable energy development or high-speed rail. And we who do the studies – at least we who do environmental impact analyses – haven’t done a thing to discourage this doofusity. We’ve happily drawn our fees doing bogus studies that make our clients’ projects look benign – maybe stretching them out for quite awhile and sucking as much money out of them as we can, but never, never, never allowing them to suggest that a project is a bad idea.

And after all, how could we? We’d be fired if we did.

I don’t know much about the Keystone XL, but I do know that two years isn’t too long to study the potential impacts of such a project, particularly when it will presumably have the effect of accelerating the despoliation of the Canadian landscape overlying the tar sands, with all its attendant effects on water and air quality, wilderness values, wildlife, First Nations rights, and other natural and cultural resources. And I wouldn’t think it entirely beyond reason for such a study – of whatever duration – to provide a rational basis for concluding that on balance the U.S. government ought not to be a party to the scheme.

Except, of course, that such studies don't provide a rational basis for anything. They have long since become so unreliable, so biased, so untrustworthy as to be useless.

Which still doesn’t lead reasonably to the conclusion that two years’ study is enough, though; it’s probably way too much.

“They’ve had TWO YEARS to study the impacts of that pipeline!” some talking head (Rick Perry, I think; I couldn’t see the screen) was saying with disgust. “That’s ENOUGH! It’s time to APPROVE IT!”

I assume the subject was the Keystone XL Pipeline. The thought that ran through my head was: “does it never occur to this doofus that one might study something for two years and conclude that it was a bad idea?”

Of course I know that it would not – particularly if the doofus was Perry, but quite likely if it was almost any other American citizen. We’ve become used to the idea that studies – particularly things like environmental impact assessments – aren’t really supposed to TEACH us anything or provide a basis for making informed decisions; they’re just things that have to be gone through, part of the price of doing business, on the way to doing what we’ve already decided to do. Sometimes, of course, we don’t bother to do studies at all (case in point: invading Iraq without thinking about what to do afterwards). Other times we waive planning studies or attenuate them into near-nonexistence (case in point: Deepwater Horizon). But even when we do them we don’t take them seriously, and don’t entertain the idea that they might lead us to re-think our initial prejudices.

Unfortunately, it’s not just the Rick Perrys of the world who think and act this way. The Obama administration has been – and continues to be – just as big a bunch of doofuses (doofi?) when it comes to its own pet projects, be they renewable energy development or high-speed rail. And we who do the studies – at least we who do environmental impact analyses – haven’t done a thing to discourage this doofusity. We’ve happily drawn our fees doing bogus studies that make our clients’ projects look benign – maybe stretching them out for quite awhile and sucking as much money out of them as we can, but never, never, never allowing them to suggest that a project is a bad idea.

And after all, how could we? We’d be fired if we did.

I don’t know much about the Keystone XL, but I do know that two years isn’t too long to study the potential impacts of such a project, particularly when it will presumably have the effect of accelerating the despoliation of the Canadian landscape overlying the tar sands, with all its attendant effects on water and air quality, wilderness values, wildlife, First Nations rights, and other natural and cultural resources. And I wouldn’t think it entirely beyond reason for such a study – of whatever duration – to provide a rational basis for concluding that on balance the U.S. government ought not to be a party to the scheme.

Except, of course, that such studies don't provide a rational basis for anything. They have long since become so unreliable, so biased, so untrustworthy as to be useless.

Which still doesn’t lead reasonably to the conclusion that two years’ study is enough, though; it’s probably way too much.

Thursday, January 12, 2012

"Indian Sacred Sites"

There’s a good deal of discussion around Washington DC these days – particularly in the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture, with encouragement from the White House – about “Indian Sacred Sites.” It’s pretty widely recognized that President Clinton’s 1996 Executive Order 13007 on the subject hasn’t accomplished much, so several gaggles of government lawyers and subject matter specialists, together with political appointees who may be either, both, or neither, are pondering what might be done to make it work. After, in some cases, extensive and ponderously documented rounds of “listening sessions” with the tribes. Is there anything more childish, demeaning, and flatly insulting than a government-sponsored “listening session?” But I digress.

Executive Order 13007 was issued in the wake of, and in response to, the Supreme Court’s deeply unfortunate decision in Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1) . This decision was rendered on a case involving a proposed Forest Service road through what the Karuk, Yurok, Hoopa and Tolowa Tribes of northern California refer to in English simply and respectfully as “the high country” – a craggy ridge on the top of the North Coast Range where tribal people go to gather and make medicine and to communicate with the spirit world. The Supremes found, in essence, that blasting the road through the area would not violate the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution – it would not “prohibit” the tribes from practicing their religion. They’d just have to dodge the trucks.

Unable to get Congress to do anything (even back then!) about what the Supremes had decreed, the tribes turned to the White House; President Clinton listened, and Executive Order 13007 was the result. Its laudable intent was to require federal agencies like the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to do what they could, within the framework of law and policy, to protect the physical integrity of places that tribes regard as spiritually significant, and to guarantee – again within reason – that tribal religious practitioners could gain access to and use such places. But it employed some unfortunate words, some of whose interpretation produced some unfortunate definitions, that have complicated efforts to implement it. I think that those involved in re-thinking “sacred sites” management today would be well advised to ponder these words and definitions, because without somehow resolving their inherent contradictions, there is little hope for achieving the executive order’s purposes.

“Site”

Though the executive order contains a number of problematical terms, the three that are perhaps most troubling make up its title. Taking the last first: what is a “site?”

“Site” is not always very meaningful as a division of tribal geography. Tribes usually occupied and used fairly large territories with somewhat vaguely defined boundaries; tribal territories could and did often overlap. Within these territories there were – and are – some fairly well-defined geographic features (River valley X; mountain Y), and many others that were not so well defined. Most land was not formally owned by individuals, so there was little or no need for the strict demarcation of boundaries. As a result, even an obvious landscape element like a mountain might have ambiguous boundaries. It’s obvious where the top of Mt. Everest is, but where are its feet?

In this sort of environment, with this sort of spatial ambiguity, what constitutes a “site?” Is a mountain a “site?” A river valley? Or does it have to be something smaller, with clearer boundaries? If so, how small does it have to be, and how clearly defined must its boundaries be? Given that tribes did not usually assign tightly defined boundaries, what is the basis for defining them?

In Section 1(b)(iii), the drafters of the executive order told us that to be a “site” a place must be “specific,” “discrete,” and “narrowly delineated.” “Specific” makes sense: a given site must be this site, and not confused with that site. But what does “discrete” mean? Dictionary.com says the word means “apart or detached from others, separate, distinct.” But this is exactly what many places viewed by tribes as “sacred” are not. The site known as Panther Meadows in northern California, for instance – well known as a place of spiritual power among the Wintu and other local tribes, is on – and therefore clearly not separate, distinct, or detached from – Mt. Shasta, which is also (with very ambiguous boundaries) regarded as a spiritual place. This sort of thing is quite common, and is hardly unique to Indian tribes. Consider the Sea of Galilee, for instance – surely a “sacred site” for Christians, but containing within it the shoreline where the loaves and fishes were multiplied, the rock outcrop on which Jesus told Peter he would be the rock on which his church would be built, the water on which Jesus walked, and so on. If we were applying the executive order in Israel, would we say that the Sea of Galilee is not a Christian sacred site because it is so indiscrete as to contain all those other sites? “Narrowly delineated” raises even more questions. Delineated by whom, on what basis, according to whose criteria?

Presumably the drafters of the executive order were trying to keep tribes from identifying the whole world, or the whole of XYZ National Park or National Forest, as a sacred site, but in pursuing this objective they effectively required that tribes abandon their own ways of viewing the landscape in favor of a Euroamerican system of metes and bounds. How does this square with the principle of respecting tribal religions that surely underlies and justifies the executive order?

“Sacred”

Dictionary.com gives us several pertinent definitions for the word “sacred:”

• devoted or dedicated to a deity or to some religious purpose; consecrated;

• entitled to veneration or religious respect by association with divinity or divine things; holy;

• pertaining to or connected with religion ( opposed to secular or profane), and

• regarded with reverence.

Some 35 years ago I had a brief but spirited debate with my good friend Fr. Francis Hezel, SJ about whether I was right to refer to Mt. Tonaachaw, on Wene Island in Chuuk, as “sacred.” Sure, Fran said, it’s where in Chuukese tradition the semi-supernatural culture-bearer Sowukachaw came in the form of a frigate bird and set up his meetinghouse; sure it’s a major landmark in the supernatural geographic lore of the islands; sure it’s metaphorically referred to as the supernatural octopus kuus, out of whose ear swim equally supernatural barracuda to protect the islands, but it’s not sacred as the term is defined in western theology. As discussed in my 2006 book Places That Count (2) , I dismissed Fran’s argument as Jesuitical hairsplitting until the statements and actions of the people living around the mountain showed me I was wrong. They respected the mountain, yes; they didn’t want other people messing with it, yes, but they were prepared – no doubt after engaging in the proper rituals – to let it be messed with for a price. Why? Because in their cultural traditions, there are ways to compensate for just about anything. So even by Dictionary.com’s rather broadminded definition, Fran was right; it’s hard to see the mountain as “consecrated,” or “devoted or dedicated to a deity” (even if Sowukachaw is deified). And while it’s certainly “connected with religion,” is that really “as opposed to” the secular or profane? This is the crux of the matter, I think. A lot of places that indigenous people regard as spiritually powerful, and entitled to respect and care on that basis, are nevertheless places where “secular” or “profane” activities go on with impunity. But to complicate things further, these “profane” activities – say, fishing, picking berries, or cutting trees – are not always or even often strictly profane; they often can be carried out only by particular kinds of people, at specific times of the day or year or cycle of the moon, accompanied by appropriate prayers or other rituals. So where do we draw the line between the “sacred” and the “profane?” And just as in forcing indigenous people to squeeze their special places into our definition of “site,” is government not forcing such people to violate the tenets of their own religions in order to receive the benefit of protection for such places? Even by the crabbed definition imposed on its language by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals (3), is this not a violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA)(4)?

Indian

Finally, there is the first word in the title: “Indian.” Setting aside the distaste for this term that arises periodically on historical and geographic ground, is it entirely fair to apply the Executive Order’s direction only to places valued only by those groups of American citizens that fall into the Order’s definition of “Indian Tribe?” That definition – in concert with those found in many other U.S. laws and regulations – is “an Indian or Alaska Native tribe, band, nation, pueblo, village, or community that the Secretary of the Interior acknowledges to exist as an Indian tribe pursuant to Public Law No. 103-454, 108 Stat. 4791.” There are good, practical reasons for that definition in other contexts – notably those involving the governance of reservations and the administration of tribal trust assets. But when it becomes the basis by which the legitimacy of a group’s assertion of a place’s spiritual significance is judged, does the Executive Order not impermissibly entangle the Secretary of the Interior in religious matters? Does it not have the Secretary, in effect, establishing which tribal religious will and will not be accorded respect? Is this quite consistent with the Establishment Clause?

Having pondered these questions ever since Executive Order 13007 was issued, I’ve sadly come to the conclusion that for all its good intentions, the Order is not worth keeping; it ought to be scrapped in favor of something else.

What else? Well, at the time of the Lyng decision, we didn’t have RFRA. Now we do, and it strikes me that a liberal reading of its prohibition on the government’s imposition of burdens on anyone’s religious practice without a compelling government interest would achieve the purposes of Executive Order 13007 without creating the complications that have kept the Order from being effective. As I’ve discussed elsewhere(5), the 10th Circuit has adopted such a reading, while the 9th Circuit has imposed a ridiculously restrictive one. It might be a lot more productive for the administration to look at ways to resolve this contradiction than to fiddle further with the deeply flawed Executive Order 13007.

Endnotes

(1) Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, 485 U.S. 439 (1988)

(2) King 2006: Places That Count: Traditional Cultural Properties in Cultural Resource Management. Altamira Press: p. 7

(3) In Navajo Nation et al v. United States Forest Service, 535 F 3d 1058 (9th Cir. 2008).

(4) 42 U.S.C. §2000bb (2006)

(5) King: What Burdens Religion? Musings on Two Recent Cases Interpreting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. 2010; Great Plains Natural Resources Journal 13:1-11

Executive Order 13007 was issued in the wake of, and in response to, the Supreme Court’s deeply unfortunate decision in Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1) . This decision was rendered on a case involving a proposed Forest Service road through what the Karuk, Yurok, Hoopa and Tolowa Tribes of northern California refer to in English simply and respectfully as “the high country” – a craggy ridge on the top of the North Coast Range where tribal people go to gather and make medicine and to communicate with the spirit world. The Supremes found, in essence, that blasting the road through the area would not violate the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution – it would not “prohibit” the tribes from practicing their religion. They’d just have to dodge the trucks.

Unable to get Congress to do anything (even back then!) about what the Supremes had decreed, the tribes turned to the White House; President Clinton listened, and Executive Order 13007 was the result. Its laudable intent was to require federal agencies like the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to do what they could, within the framework of law and policy, to protect the physical integrity of places that tribes regard as spiritually significant, and to guarantee – again within reason – that tribal religious practitioners could gain access to and use such places. But it employed some unfortunate words, some of whose interpretation produced some unfortunate definitions, that have complicated efforts to implement it. I think that those involved in re-thinking “sacred sites” management today would be well advised to ponder these words and definitions, because without somehow resolving their inherent contradictions, there is little hope for achieving the executive order’s purposes.

“Site”

Though the executive order contains a number of problematical terms, the three that are perhaps most troubling make up its title. Taking the last first: what is a “site?”

“Site” is not always very meaningful as a division of tribal geography. Tribes usually occupied and used fairly large territories with somewhat vaguely defined boundaries; tribal territories could and did often overlap. Within these territories there were – and are – some fairly well-defined geographic features (River valley X; mountain Y), and many others that were not so well defined. Most land was not formally owned by individuals, so there was little or no need for the strict demarcation of boundaries. As a result, even an obvious landscape element like a mountain might have ambiguous boundaries. It’s obvious where the top of Mt. Everest is, but where are its feet?

In this sort of environment, with this sort of spatial ambiguity, what constitutes a “site?” Is a mountain a “site?” A river valley? Or does it have to be something smaller, with clearer boundaries? If so, how small does it have to be, and how clearly defined must its boundaries be? Given that tribes did not usually assign tightly defined boundaries, what is the basis for defining them?

In Section 1(b)(iii), the drafters of the executive order told us that to be a “site” a place must be “specific,” “discrete,” and “narrowly delineated.” “Specific” makes sense: a given site must be this site, and not confused with that site. But what does “discrete” mean? Dictionary.com says the word means “apart or detached from others, separate, distinct.” But this is exactly what many places viewed by tribes as “sacred” are not. The site known as Panther Meadows in northern California, for instance – well known as a place of spiritual power among the Wintu and other local tribes, is on – and therefore clearly not separate, distinct, or detached from – Mt. Shasta, which is also (with very ambiguous boundaries) regarded as a spiritual place. This sort of thing is quite common, and is hardly unique to Indian tribes. Consider the Sea of Galilee, for instance – surely a “sacred site” for Christians, but containing within it the shoreline where the loaves and fishes were multiplied, the rock outcrop on which Jesus told Peter he would be the rock on which his church would be built, the water on which Jesus walked, and so on. If we were applying the executive order in Israel, would we say that the Sea of Galilee is not a Christian sacred site because it is so indiscrete as to contain all those other sites? “Narrowly delineated” raises even more questions. Delineated by whom, on what basis, according to whose criteria?

Presumably the drafters of the executive order were trying to keep tribes from identifying the whole world, or the whole of XYZ National Park or National Forest, as a sacred site, but in pursuing this objective they effectively required that tribes abandon their own ways of viewing the landscape in favor of a Euroamerican system of metes and bounds. How does this square with the principle of respecting tribal religions that surely underlies and justifies the executive order?

“Sacred”

Dictionary.com gives us several pertinent definitions for the word “sacred:”

• devoted or dedicated to a deity or to some religious purpose; consecrated;

• entitled to veneration or religious respect by association with divinity or divine things; holy;

• pertaining to or connected with religion ( opposed to secular or profane), and

• regarded with reverence.

Some 35 years ago I had a brief but spirited debate with my good friend Fr. Francis Hezel, SJ about whether I was right to refer to Mt. Tonaachaw, on Wene Island in Chuuk, as “sacred.” Sure, Fran said, it’s where in Chuukese tradition the semi-supernatural culture-bearer Sowukachaw came in the form of a frigate bird and set up his meetinghouse; sure it’s a major landmark in the supernatural geographic lore of the islands; sure it’s metaphorically referred to as the supernatural octopus kuus, out of whose ear swim equally supernatural barracuda to protect the islands, but it’s not sacred as the term is defined in western theology. As discussed in my 2006 book Places That Count (2) , I dismissed Fran’s argument as Jesuitical hairsplitting until the statements and actions of the people living around the mountain showed me I was wrong. They respected the mountain, yes; they didn’t want other people messing with it, yes, but they were prepared – no doubt after engaging in the proper rituals – to let it be messed with for a price. Why? Because in their cultural traditions, there are ways to compensate for just about anything. So even by Dictionary.com’s rather broadminded definition, Fran was right; it’s hard to see the mountain as “consecrated,” or “devoted or dedicated to a deity” (even if Sowukachaw is deified). And while it’s certainly “connected with religion,” is that really “as opposed to” the secular or profane? This is the crux of the matter, I think. A lot of places that indigenous people regard as spiritually powerful, and entitled to respect and care on that basis, are nevertheless places where “secular” or “profane” activities go on with impunity. But to complicate things further, these “profane” activities – say, fishing, picking berries, or cutting trees – are not always or even often strictly profane; they often can be carried out only by particular kinds of people, at specific times of the day or year or cycle of the moon, accompanied by appropriate prayers or other rituals. So where do we draw the line between the “sacred” and the “profane?” And just as in forcing indigenous people to squeeze their special places into our definition of “site,” is government not forcing such people to violate the tenets of their own religions in order to receive the benefit of protection for such places? Even by the crabbed definition imposed on its language by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals (3), is this not a violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA)(4)?

Indian

Finally, there is the first word in the title: “Indian.” Setting aside the distaste for this term that arises periodically on historical and geographic ground, is it entirely fair to apply the Executive Order’s direction only to places valued only by those groups of American citizens that fall into the Order’s definition of “Indian Tribe?” That definition – in concert with those found in many other U.S. laws and regulations – is “an Indian or Alaska Native tribe, band, nation, pueblo, village, or community that the Secretary of the Interior acknowledges to exist as an Indian tribe pursuant to Public Law No. 103-454, 108 Stat. 4791.” There are good, practical reasons for that definition in other contexts – notably those involving the governance of reservations and the administration of tribal trust assets. But when it becomes the basis by which the legitimacy of a group’s assertion of a place’s spiritual significance is judged, does the Executive Order not impermissibly entangle the Secretary of the Interior in religious matters? Does it not have the Secretary, in effect, establishing which tribal religious will and will not be accorded respect? Is this quite consistent with the Establishment Clause?

Having pondered these questions ever since Executive Order 13007 was issued, I’ve sadly come to the conclusion that for all its good intentions, the Order is not worth keeping; it ought to be scrapped in favor of something else.

What else? Well, at the time of the Lyng decision, we didn’t have RFRA. Now we do, and it strikes me that a liberal reading of its prohibition on the government’s imposition of burdens on anyone’s religious practice without a compelling government interest would achieve the purposes of Executive Order 13007 without creating the complications that have kept the Order from being effective. As I’ve discussed elsewhere(5), the 10th Circuit has adopted such a reading, while the 9th Circuit has imposed a ridiculously restrictive one. It might be a lot more productive for the administration to look at ways to resolve this contradiction than to fiddle further with the deeply flawed Executive Order 13007.

Endnotes

(1) Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, 485 U.S. 439 (1988)

(2) King 2006: Places That Count: Traditional Cultural Properties in Cultural Resource Management. Altamira Press: p. 7

(3) In Navajo Nation et al v. United States Forest Service, 535 F 3d 1058 (9th Cir. 2008).

(4) 42 U.S.C. §2000bb (2006)

(5) King: What Burdens Religion? Musings on Two Recent Cases Interpreting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. 2010; Great Plains Natural Resources Journal 13:1-11

Friday, January 06, 2012

Consultation

The word “consultation” is used in dozens, maybe hundreds or thousands of United States laws, regulations, guidelines, standards , and probably comic books, referring to something that should be done on the way to making decisions. Federal agency officials are regularly directed to consult with other federal officials, with federally recognized Indian tribes, with state and local government agencies, with subject-matter experts, with specific concerned parties, and sometimes even with the general public. These officials are usually told to initiate consultation early in planning, and are occasionally (though not often) told to bring it to some kind of conclusion before actually making a decision. Very occasionally they are told that consultation is supposed to influence their decisions, and there is a good deal of case law indicating that they should keep an administrative record documenting their consultation.

However, there is little official direction about just how an agency ought to consult – that is, about what “consultation” means.

I think that’s a problem that’s likely to render meaningless all the cogitation, head-scratching and paper-production that’s going on in the agencies these days – sometimes with reference to “tribal consultation,” sometimes with respect to “sacred sites” management, sometimes (though rarely, it seems) with respect simply to how the public – the voters and taxpayers – ought to be involved in their government’s decision-making.

So here’s some unsolicited advice for the White House, the Department of the Interior, the Forest Service, and all the others who are worrying about such matters:

(1) Give some thought to what “consultation” ought to mean.

(2) Once you figure it out:

(a) Try to make sure your administrative procedures let or even make it happen; and

(b) Give your people some explicit direction and training in how to do it.

I don’t think that item #1 above is all that difficult. It comes down to a simple rule, articulated long ago by a guy whose name a lot of politicians like to invoke these days, which goes like this:

"Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them"

(Jesus of Nasareth, according to Matthew 7:12).

Or in its common simplified form: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Think about how you would want to be consulted if government was going to do something potentially affecting you. Ask yourself:

• Would you be satisfied getting a letter saying “We’re planning to do XYZ; if you have any comments, please send them in within 30 days?”

• Would it be OK with you for the government to take your comments, task somebody with writing dismissive responses to them, and ignoring them?

• Would you think it reasonable for the government to establish in advance, and unilaterally, what could and couldn’t be discussed in the course of consultation?

• Do you think that it would be helpful for the government to send low-level employees or contractors to chat with you, who couldn’t do a thing to accommodate your concerns?

• Would you be satisfied with “listening sessions” that collected your concerns but didn’t engage you in trying to do anything about them?

No? I didn’t think so. But all the above (and other things just as ineffective and insulting) are things that government agencies routinely do under the guise of “consultation.”

So how would you like to be consulted? I don’t know about you, but I’d like to be consulted in the following manner:

1. Explain to me, in words I can understand, what it is you’re thinking of doing. Do this before you’ve decided to do it, or invested much time and money in planning to do it.

2. Communicate with me, back and forth, about

a. Why you want to do what you want to do;

b. What its purpose is, and why that purpose is justified;

c. Alternative ways of achieving the purposes that justify doing it;

d. Any problems I have with your doing it;

e. Ways to resolve my problems; and

f. If you don’t think you can resolve my problems, why you can’t.

3. If possible, reach agreement with me about how my problems will be addressed.

4. Do what you’ve agreed to do.

5. If we can’t reach agreement, document how we’ve tried to do so, and do whatever you can do to address my problems.

That, it seems to me, is what consultation ought to entail, and what government officials ought to be directed, instructed, and trained in doing.

Another thing they need to be directed, instructed, and trained about – because it’s critical to effective consultation – is thinking in advance about the intellectual baggage that they, the government officials, and their advisors, contractors, and experts, bring to the consultation table. This advice comes from a source (among others) that’s not quite as hoary as the one cited above, but it’s long enough in the tooth, and popular enough, that it ought not be the mystery it seems to be to some government officials and consultants:

“Your perceptions are likely to be one-sided, and you may not be listening or communicating adequately”

(Roger Fisher & William Ury: Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, 2nd edition, Penguin 1991:22).

One of the great frustrations that Indian tribes have in “consulting” with some federal land management agencies about cultural resource issues is that they find themselves consulting with archaeologists, or with managers who are influenced by archaeologists, who expect them to phrase their cultural concerns in archaeological terms – or who at least themselves can’t get beyond archaeological world views. So the tribes are supposed to be happy that you’ve sent out archaeologists to find all the “sites” and designed your project to “avoid” them? That may make sense to your archaeologist, Ms. Manager, but it’s unlikely to carry much weight with a tribe. Citizens seeking to consult about impacts on their neighborhoods are often similarly frustrated by government representatives who think only about the historic or architectural value of buildings, or about the economics of a community’s lifeways.

A critical thing that agency people need to consider going into a consultation is: “How are the people I’m consulting likely to perceive the issues?” And they ought to prepare themselves – through study, through the composition of their consulting team, through simply keeping their minds open and sorting through their own beliefs, assumptions, and biases – to understand those perceptions and deal with them thoughtfully.

These things may seem intuitively obvious; it may seem unnecessary even to mention them. But I think that if they’re not thought about and addressed explicitly, all the direction in the world to “consult” isn’t going to do any good.

However, there is little official direction about just how an agency ought to consult – that is, about what “consultation” means.

I think that’s a problem that’s likely to render meaningless all the cogitation, head-scratching and paper-production that’s going on in the agencies these days – sometimes with reference to “tribal consultation,” sometimes with respect to “sacred sites” management, sometimes (though rarely, it seems) with respect simply to how the public – the voters and taxpayers – ought to be involved in their government’s decision-making.

So here’s some unsolicited advice for the White House, the Department of the Interior, the Forest Service, and all the others who are worrying about such matters:

(1) Give some thought to what “consultation” ought to mean.

(2) Once you figure it out:

(a) Try to make sure your administrative procedures let or even make it happen; and

(b) Give your people some explicit direction and training in how to do it.

I don’t think that item #1 above is all that difficult. It comes down to a simple rule, articulated long ago by a guy whose name a lot of politicians like to invoke these days, which goes like this:

"Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them"

(Jesus of Nasareth, according to Matthew 7:12).

Or in its common simplified form: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Think about how you would want to be consulted if government was going to do something potentially affecting you. Ask yourself:

• Would you be satisfied getting a letter saying “We’re planning to do XYZ; if you have any comments, please send them in within 30 days?”

• Would it be OK with you for the government to take your comments, task somebody with writing dismissive responses to them, and ignoring them?

• Would you think it reasonable for the government to establish in advance, and unilaterally, what could and couldn’t be discussed in the course of consultation?

• Do you think that it would be helpful for the government to send low-level employees or contractors to chat with you, who couldn’t do a thing to accommodate your concerns?

• Would you be satisfied with “listening sessions” that collected your concerns but didn’t engage you in trying to do anything about them?

No? I didn’t think so. But all the above (and other things just as ineffective and insulting) are things that government agencies routinely do under the guise of “consultation.”

So how would you like to be consulted? I don’t know about you, but I’d like to be consulted in the following manner:

1. Explain to me, in words I can understand, what it is you’re thinking of doing. Do this before you’ve decided to do it, or invested much time and money in planning to do it.

2. Communicate with me, back and forth, about

a. Why you want to do what you want to do;

b. What its purpose is, and why that purpose is justified;

c. Alternative ways of achieving the purposes that justify doing it;

d. Any problems I have with your doing it;

e. Ways to resolve my problems; and

f. If you don’t think you can resolve my problems, why you can’t.

3. If possible, reach agreement with me about how my problems will be addressed.

4. Do what you’ve agreed to do.

5. If we can’t reach agreement, document how we’ve tried to do so, and do whatever you can do to address my problems.

That, it seems to me, is what consultation ought to entail, and what government officials ought to be directed, instructed, and trained in doing.

Another thing they need to be directed, instructed, and trained about – because it’s critical to effective consultation – is thinking in advance about the intellectual baggage that they, the government officials, and their advisors, contractors, and experts, bring to the consultation table. This advice comes from a source (among others) that’s not quite as hoary as the one cited above, but it’s long enough in the tooth, and popular enough, that it ought not be the mystery it seems to be to some government officials and consultants:

“Your perceptions are likely to be one-sided, and you may not be listening or communicating adequately”

(Roger Fisher & William Ury: Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In, 2nd edition, Penguin 1991:22).

One of the great frustrations that Indian tribes have in “consulting” with some federal land management agencies about cultural resource issues is that they find themselves consulting with archaeologists, or with managers who are influenced by archaeologists, who expect them to phrase their cultural concerns in archaeological terms – or who at least themselves can’t get beyond archaeological world views. So the tribes are supposed to be happy that you’ve sent out archaeologists to find all the “sites” and designed your project to “avoid” them? That may make sense to your archaeologist, Ms. Manager, but it’s unlikely to carry much weight with a tribe. Citizens seeking to consult about impacts on their neighborhoods are often similarly frustrated by government representatives who think only about the historic or architectural value of buildings, or about the economics of a community’s lifeways.

A critical thing that agency people need to consider going into a consultation is: “How are the people I’m consulting likely to perceive the issues?” And they ought to prepare themselves – through study, through the composition of their consulting team, through simply keeping their minds open and sorting through their own beliefs, assumptions, and biases – to understand those perceptions and deal with them thoughtfully.

These things may seem intuitively obvious; it may seem unnecessary even to mention them. But I think that if they’re not thought about and addressed explicitly, all the direction in the world to “consult” isn’t going to do any good.

Wednesday, January 04, 2012

Highway to Hell: Worth Reading

On the Highway to Hell: Thoughts on the Unintended Consequences for Portable Antiquities of § 11(1) Austrian Denkmalschultzgesetz. Raimund Karl, The Historic Environment Policy and Practice 2:2:111-133, 2011

Particularly if you’re a government employee and think yourself involved in “heritage management,” or if you’re an archaeological, historic preservation, or environmental activist thinking to promote better laws to protect the cultural environment, you need to read this excellent article. It’s about Austria, but the lessons it embodies are relevant to any country.

As Karl details, Austrian law includes a scheme under which people who find antiquities are required to report them to the National Heritage Agency Bundesdenkmalamt (BDA). The BDA is also responsible for licensing excavations for archaeological material, and under its current procedures (circa 1999) can issue licenses only to formally qualified archaeologists.

Giving a little thought to the matter, one might predict that this policy would drive artifact collecting underground (as it were). Karl rather elegantly demonstrates that this has precisely been the result. Collectors do not stop digging or collecting; they simply stop reporting, because to do so would be to pre-emptively admit to breaking the law. Karl’s paper features a comparison of finds reporting statistics from Austria with equivalent data from England and Wales – where the much more liberal Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) is in effect, and from Scotland, whose policies are more like Austria’s. The results are impressive: reported finds have increased dramatically under the PAS, while they have remained flat or declined in Austria and Scotland; moreover the absolute number of reports in England and Wales, adjusted for land area and population – is vastly higher than in Austria since institution of that country’s restrictive policies. Karl also reports his research into the actual behavior and perceptions of metal detector-using collectors in Austria, which indicates that they are extremely active, have substantial collections, do not for the most part sell them, often keep excellent records, and would like to cooperate with archaeologists if they wouldn’t be thrown in the slammer for doing so. He also shows that most metal detectorists do not dig very deeply, instead collecting mostly from the plow zone – which is routinely scraped away by archaeologists as a first step in the conduct of controlled excavations! There seems to be a lot of room for cooperation between archaeologists and collectors in Austria, but as the law is currently construed, it can’t happen legally.

I feel sure that Austria is in no way unique in this regard. Certainly my informal experience with collectors in the U.S. suggests a similar conclusion about the potential for cooperation and its suppression by restrictive regulation.

Particularly if you’re a government employee and think yourself involved in “heritage management,” or if you’re an archaeological, historic preservation, or environmental activist thinking to promote better laws to protect the cultural environment, you need to read this excellent article. It’s about Austria, but the lessons it embodies are relevant to any country.

As Karl details, Austrian law includes a scheme under which people who find antiquities are required to report them to the National Heritage Agency Bundesdenkmalamt (BDA). The BDA is also responsible for licensing excavations for archaeological material, and under its current procedures (circa 1999) can issue licenses only to formally qualified archaeologists.

Giving a little thought to the matter, one might predict that this policy would drive artifact collecting underground (as it were). Karl rather elegantly demonstrates that this has precisely been the result. Collectors do not stop digging or collecting; they simply stop reporting, because to do so would be to pre-emptively admit to breaking the law. Karl’s paper features a comparison of finds reporting statistics from Austria with equivalent data from England and Wales – where the much more liberal Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) is in effect, and from Scotland, whose policies are more like Austria’s. The results are impressive: reported finds have increased dramatically under the PAS, while they have remained flat or declined in Austria and Scotland; moreover the absolute number of reports in England and Wales, adjusted for land area and population – is vastly higher than in Austria since institution of that country’s restrictive policies. Karl also reports his research into the actual behavior and perceptions of metal detector-using collectors in Austria, which indicates that they are extremely active, have substantial collections, do not for the most part sell them, often keep excellent records, and would like to cooperate with archaeologists if they wouldn’t be thrown in the slammer for doing so. He also shows that most metal detectorists do not dig very deeply, instead collecting mostly from the plow zone – which is routinely scraped away by archaeologists as a first step in the conduct of controlled excavations! There seems to be a lot of room for cooperation between archaeologists and collectors in Austria, but as the law is currently construed, it can’t happen legally.

I feel sure that Austria is in no way unique in this regard. Certainly my informal experience with collectors in the U.S. suggests a similar conclusion about the potential for cooperation and its suppression by restrictive regulation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)