The potential client – representing a U.S. government agency

– had a simple request:

“We want to hire you to draft a nomination for the

HappyDrone House (not its real name) to the National Register of Historic

places.”

As a proper profit-seeking consultant, my response should

have been: “Great! Let’s talk about

it!” But as some readers know, I’m not

very good at being a proper profit-seeking consultant. So my actual response was:

“Why do you want to do a thing like that?”

The potential client – let’s call him PC – responded that

the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) required his agency to nominate

places under its jurisdiction and control.

“Ummm,” I said, still being difficult, “can you give me a

citation for that requirement?”

“Sure,” he replied – more knowledgeably than most who call

me about things like this. “Section

110(a)(2) requires agencies to establish preservation programs, and those

programs are to ensure – and I quote – ‘that historic properties under the

jurisdiction or control of the agency are identified, evaluated, and nominated

to the National Register.’”

Oh

my, I thought. Why do I bother to write

all those books? Section 110(a)(2) and

its registration “requirement” are discussed in several of my tomes, most

recently (I think) on pages 234-5 of the 4th edition of Cultural Resource Laws and Practice

(Altamira Press 2013).

But

maybe I haven’t been straightforward enough, so let me try again.

As

I explained to PC – finally, I think, talking him out of nominating the house,

but maybe only persuading him to go to another consultant – you need to

understand Section 110(a)(2) in its historical, political, context. The subsection he quoted is derived from

Executive Order 11593, issued by President Nixon in 1971[1]. In those days Section 106 of NHPA required

attention only to places included in the National Register, which caused

all kinds of wasteful nonsense. The executive

order told all executive branch agencies to do two things:

1.

Get busy and nominate everything under their

jurisdiction and control to the Register – by July 1, 1973, no less; and

2.

Until everything was duly nominated and listed,

address impacts on eligible places just as though such places were

already listed.

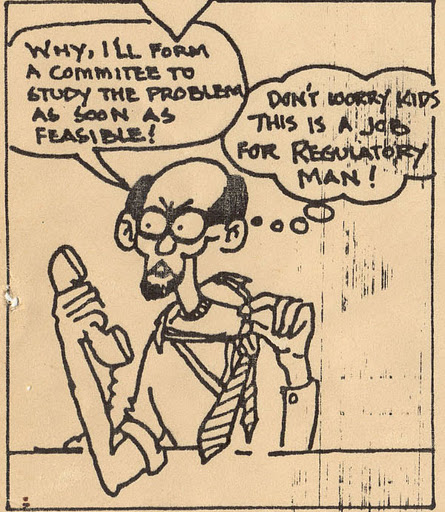

Of course, the first requirement was absurd,

and nobody (with the alleged, possibly apocryphal, exception of the Tea Tasting

Commission[2])

carried it out. Agencies focused on the order's second requirement -- to consider their impacts on eligible but unlisted places. They did this with guidance from the National

Park Service (NPS) and Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP); for better or worse

this was the beginning of the modern “cultural resource management” (CRM) industry.

In 1976 Section 106 itself was amended to comport with

reality; agencies were required to take effects into account both on listed

places and on those that simply meet the National Register’s eligibility

criteria (36 CFR 60.4). This canonized

and regularized by-then existing practice.

At the same time, though, Congress added the beginnings of Section 110

to the law, essentially picking up the executive order’s language and directing

agencies – without a time limit – to nominate “all” eligible properties under

their jurisdiction or control.

Getting rid of the deadline was an improvement, but the

requirement was still a silly one. It

assumed that somehow or other agencies were going to spend the vast amounts of

money necessary to (ostensibly) find everything under their jurisdictions that

met objective standards of historical significance (whatever those might be) and

prepare the ponderous documentation required to nominate them to the

Register.

And that parenthetical “ostensibly”

is important. History hasn’t stopped, so new things become “historic” every

day. Technology changes, too, so we’re

able to find and interpret historic (and prehistoric) things today that we couldn’t find in

the 1970s, or 90s. And concepts of

historic significance change as well; we do learn stuff, and change our

minds about what’s important. That’s not

a bad thing, however inconvenient it may be for recordkeeping.

Finally, historic places aren’t the only things that federal

agencies need to keep track of, and the National Register is not the only, or

necessarily the best, way to keep track of them. In the 1980s, for example, agencies like the

Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management organized sophisticated

geographic information systems (GIS), to map and plot and keep track of all

kinds of environmental variables. These

systems didn’t (and still don’t) interface very well with the National

Register, but they are far more efficient and effective management tools than

the Register will ever think of being.

So nobody paid much attention to Section 110’s requirements

– which was kind of too bad, because the requirements to identify

things, and maybe to evaluate them, made a good deal of sense, even if the

stuff about nominating them didn’t.

So around 1990, when work began on what would become the 1992

amendments to NHPA, a few of us suggested that some amendments to Section 110

were in order.

I had recently quit my job at the ACHP – the proximate cause of my resignation was my objection

to a settlement agreement in a court case involving National Register

nominations in New Mexico – and was doing pro

bono work on the proposed amendments.

I proposed to do away with the requirement to nominate all historic

properties, leaving just the requirements to identify and evaluate, and then

adding requirements about preferential use, management, consultation,

agreements, and addressing the interests of tribes.

NPS, of course, screamed bloody

murder. How could anyone propose that places

shouldn’t be nominated to the all-holy National Register? No right minded citizen, that was for sure –

it was just that King guy, who – the Keeper of the Register still assures

people of this – just hates the Register.

(For the record, I don’t hate the Register; I just think

it’s a simpleminded institution whose time has come and gone, and that we’d

have a better national historic preservation program if we shucked it. But I digress)

As always in matters political (the current beliefs of some congresspeople notwithstanding), compromise was in order, and

in the end the amendments wound up including language about consultation,

agreements and such, but making only a small change to the bit about

nomination: deleting the word “all.”

So yes, PC, agencies must have programs that provide for –

among many other things (like consultation, agreements, etc.), identification,

evaluation, and nomination of historic places to the Register, but they don’t

have to nominate “all” such places.

The result, if an agency wants to devote a little thought

and creativity to the matter, is that an agency really has a lot of flexibility

in how it keeps track of its historic places.

An agency’s program can, for example, provide for identifying historic

properties (and/or the probability of such properties) as part of its overall

GIS, evaluating them when there’s a need to – for instance, when some sort of

conflict with their management is looming – and nominating them only when

there’s some pragmatic reason for doing so.

And there are – unfortunately, I think – some

pragmatic reasons for nomination. For

example, if you’re transferring a building out of federal ownership and want to

encourage a private party to rehabilitate it, nominating it can set the private

recipient up for tax benefits if he or she rehabilitates it in accordance with

preservation standards. In such cases,

sure, nomination may be worth the posterior discomfort inherent in its doing.

But the bottom line is that the NHPA does not require

agencies to nominate whatever they control, or really to nominate anything at

all. Agencies must have programs that

provide for nomination – among many more useful activities. My recommendation to PC was that he focus on

those activities rather than wasting taxpayer dollars on nomination.

So I lost the contract.

Oh well.

[2]

Actually the Board of Tea Examiners, disbanded by act of Congress in 1996, see http://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/26/nyregion/congress-votes-to-end-tea-tasting-board.html

No comments:

Post a Comment