By Tom King

Posted 11/25/2014 in the

Huffington Post, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/tom-king/pity-the-dugongs-us-dod-s_b_6203790.html

Dugongs?

The

Okinawa Dugong (Dugong dugon) is a large, fleshy marine mammal related to the

Manatee (Trichechus sp.). Its dwindling population lives in sheltered waters

around the island of Okinawa in Japan, feeding on beds of seagrass.

Traditionally, the dugong is a sacred animal on Okinawa, associated with the

ancient origins of the Okinawan people and with their continuing welfare. As a

result, the dugong is officially listed as a "Natural Monument" under

Japan's "Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties" (LPCP).

The

Henoko/Oura Bay Project

The U.S.

Department of Defense (DOD), under pressure to reduce its military footprint on

Okinawa , has proposed to consolidate operations at Camp Schwab, a Marine Corps

base on Henoko and Oura Bays on the island's east coast. The proposal involves

runway expansion over part of one of the few remaining seagrass beds available

for the dugong. Per treaties with the U.S., the Japanese government supports

the proposal.

Okinawa

residents and Japanese environmentalists have fought the project, but have been

thwarted by Japan's relatively weak and centralized environmental review laws,

which give concerned citizens little opportunity to influence decision making.

So the Japan Environmental Lawyers' Federation (JELF) and its allies turned to

U.S. law. With the help of Earthjustice , in 2003 they found an obscure legal

handle -- Section 402 of the U.S. National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) .

Sections

106 and 402 of NHPA

The

best-known section of the NHPA is Section 106, which requires U.S. government

agencies to "take into account" the effects of their domestic

activities -- such as highway construction, military base management, and

energy development -- on historic places, which are defined as places included

in or eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. Regulations of the

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) spell out how this is to be

done - it involves consultation with interested parties, studies to identify

historic places and determine how they may be affected, and negotiation of

agreements about how to deal with the effects.

Section

402 of the law is the international version of Section 106; it requires U.S.

agencies to take into account the effects of their proposed actions on

resources listed in any host nation's equivalent of the U.S. National Register.

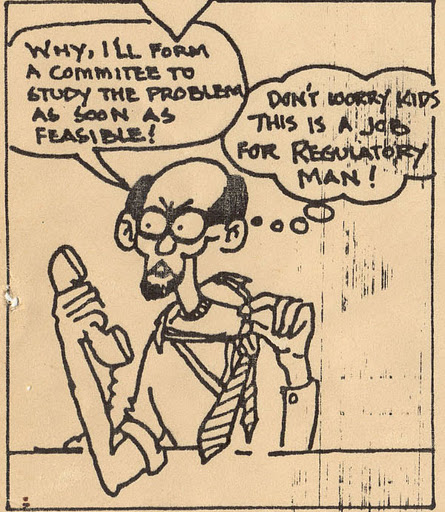

However, there are no regulations governing compliance with Section 402, so

agencies tend to ignore it.

As did DOD

in planning its expanded base at Henoko and Oura Bays.

The 2003

Litigation

On behalf

of JELF and its allies, in 2003 Earthjustice filed suit in U.S. District Court

in San Francisco, charging that DOD was in violation of NHPA Section 402.

Obviously, they charged, destroying the habitat of the dugong would have

serious impact on the animals, whose listing under Japan's LPCP brought them

under NHPA's protection.

The U.S.

government initially responded that Section 402 didn't apply, because Japan's

LPCP wasn't "equivalent" to the U.S. NHPA. Why not? Well, because it

didn't use quite the same words, and because it includes animals, like dugongs,

while the U.S. National Register does not.

The

plaintiffs pointed out that "equivalent" does not mean

"identical," and showed that while the U.S. Register indeed doesn't

list animals per se, it does list places made historically significant through

association with animals, such as traditional fishing sites. The lists, they

argued, and the laws that govern them, are functional equivalents.

The court

agreed, and directed DOD to refrain from pursuing the project until it had

complied with Section 402 - which meant, the court said, following the basic

outline of Section 106 review in partnership with the Japanese government and

"other relevant private organizations and individuals."

DOD's

Response

On April 16

of this year, DOD informed the court that it had done its work and determined

that the base expansion would have "no adverse effect" on the

dugongs. But the procedures it employed to reach this determination seem to

bear only rhetorical resemblance either to Section 106 review as conducted in

the U.S., or to the direction of the court.

DOD says

its determination is based on studies done by various professionals - but it

refuses to release their reports, or even their full titles. I've personally

made two requests for the key report, and been stiffed by DOD both times. They

haven't even told me to seek it under the Freedom of Information Act -- the

government's usually favored means of keeping the public in the dark while

pretending "transparency."

DOD says

it "consulted," but it did so only with Japanese government agencies

and with its own selected groups and individuals. It consulted neither with any

of any of the plaintiffs or other opposition groups or with the general

Okinawan public - or even notify them as to what was going on. I've seen no

evidence that they even consulted with the Advisory Council on Historic

Preservation, whose Section 106 regulations lay out the processes that the

court said DOD should emulate.

DOD relied

on essentially uncontrolled secondary data and a questionable environmental

study conducted by the Japanese government to conclude that dugongs really

don't use Henoko or Oura Bays very much, and if they do, well, they won't be

bothered much by the construction and operation of the base. And while it

assures the court that the project will have no adverse effect on the dugongs,

it promises a good many measures supposedly designed to mitigate the adverse

effects it says won't happen. But unlike under Section 106 of NHPA, where binding

agreements are executed on how mitigation will be done, DOD simply says

"trust us."

Having now

- to its own satisfaction if to no one else's -- "complied" with

Section 402, DOD has petitioned the court to dismiss the plaintiffs' complaint.

And if the

court isn't satisfied with the quality of DOD's "compliance?" Well,

says DOD in its filings, that really doesn't matter, because the court has no

jurisdiction anyway. The base consolidation/expansion is required for purposes

of national defense and vital to our relationship with Japan, so under what DOD

calls "a universal understanding ever since George Washington's

administration," the court is barred from interfering in the executive

branch's decisions.

Whither

the Dugong?

The

plaintiffs are not impressed; they have released their own studies, which

criticize the inclusiveness and methodology of those relied on by DOD and

predict that if the project proceeds, it will likely have disastrous

consequences for the dugong. They have decried DOD's failure to consult or

reach agreements in a manner parallel to ordinary practice under Section 106 of

NHPA, and they have marshaled a considerable body of case law indicating that

DOD is drastically overreaching in its interpretation of that so-called

"universal understanding."

I'm told

that arguments will be heard in court in San Francisco next week. What will

become of the dugongs' case? Will the court find that whenever the U.S.

Department of Defense decides that national security and international

relations are involved, U.S. courts have no jurisdiction over how DOD planning

considers environmental impacts and addresses the concerns of the affected

public?

Stay

tuned. The dugong -- reported to have good hearing and long memories --

doubtless will, as though their lives depended on it.

No comments:

Post a Comment