Under Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act of

1899 (33 U.S.C. 403) and Section 404 of the Clean Water Act of 1972 (33 U.S.C.

1344), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) regulates the discharge of fill

into water bodies defined as parts of the “waters of the United

States.” Often the Corps’ Section 10/404 permit authority is the only federal “handle”

that makes a privately funded project on non-federal land subject to review

under such environmental impact assessment laws as the National Environmental

Policy Act (NEPA) and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act

(NHPA). Often this “handle” is quite a

small one in geographic terms vis-à-vis the overall project; in other words,

the discharge of fill into a water body may be a small part of a large project whose effects otherwise are not subject to U.S. government regulation.

In consultations under the NHPA, and in litigation

under both the NEPA and the NHPA, consulting parties and plaintiffs often argue that the Corps must consider the effects

of the entire project on the environment (or in the case of the NHPA, on

historic properties). The Corps typically responds that it can consider only what falls within its regulatory jurisdiction. Exactly how much this constrains the Corps’ review of impacts varies from case to case,

depending on how the Corps in each case interprets the esoteric language of its

regulatory program regulations, 33 CFR 320-338. Generally speaking, however, the Corps

position is that it can consider only effects that may occur within the “permit

area” of a given proposed discharge or stream crossing, which more or less means the waters into

which the fill will be discharged or which will be crossed by the project, plus certain appurtenant areas where things

may be done that are pretty directly related to the discharge or crossing (access road

construction, etc.).

Although the Corps' early history of success with this limited interpretation was spotty (c.f. http://crmplus.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-us-army-corps-of-engineers.html), in recent years courts have often agreed with the Corps’ view of its responsibilities. For example, in Sierra Club v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 803 F.3d 31 (D.C. Cir.

2015), the court held that the Corps was “not required to conduct NEPA analysis

of the entirety of the … pipeline, including portions not subject to federal

control or permitting.”

I think that the Corps, and the court, have confused the extent of a project's likely environmental effects with the extent of government regulatory authority. This confusion can be illustrated by reference to a hypothetical example

that I refer to as “bombing Boise[1].”

I am quite sure I outlined this hypothetical in some version of one of my ancient publications, but I can’t now locate it, and if I can’t, it’s a sure bet that

no one else can, so here it is again.

Suppose that the owner of a tract of marshland in

central Florida – call him Donald – has developed a visceral dislike for the

city of Boise, Idaho. Donald, who has far more money than he knows what to do with, decides to

wipe that city off the map. To achieve this goal, he arranges for the purchase

of an intermediate range ballistic missile with a nuclear warhead (Remember,

this is hypothetical). He plans to launch this missile toward Boise from his

marshy ranch in central Florida. To do so, he must fill some 2.5 acres of marsh

in order to create a stable launch pad. A law-abiding citizen, Donald applies

for a permit from the Corps.

Here’s the question: in considering whether to

issue Donald a permit for his project in Florida, must the Corps consider the

likely effects of doing so on the environment of Boise, Idaho? Boise is a very

long way from the waters of the U.S. into which Donald will discharge his fill.

It is certainly well outside Donald’s “permit area” as defined in the Corps’

regulations. Donald may or may not be able to get his bird off the ground, and

it may or may not be shot down by Boise’s missile defense system, but let’s set

that aside. Should the Corps consider the effects of bombing Boise when it

considers Donald’s permit application?

The court in Sierra

Club seems to say “no,” because the Corps has no “regulatory control” over what

the project in the marshes of central Florida may do to distant upland areas

like Boise.

But is regulatory control over areas of impact actually relevant?

The NEPA, at Section 102(C), directs that federal

agencies prepare statements analyzing environmental impacts of any federal

action “significantly affecting

the quality of the human environment.” The NHPA, at Section 106, says that federal

agencies must take into account the effects of their undertakings “on any district, site,

building, structure, or object that is included in or eligible for inclusion in

the National Register (of Historic

Places).” Neither statute says that agencies are to consider only effects that are

subject to their “control,” regulatory or otherwise.

In the

case of Donald’s project, arguably the Corps’ “regulatory control” extends only

to the wetlands he proposes to fill, and the adjacent or nearby areas that will

be impinged upon by roads, liquid oxygen lines, warhead containment facilities and the like. But the area in which environmental impacts may

occur if the Corps gives him the permit is much larger, surely including Boise.

Can the Corps ignore what Donald plans to do to the capital of Idaho? I

don’t think so -- regardless of the ostensibly limited extent of the Corps' regulatory control.

And of course, the Corps does have regulatory control over Donald's proposed launch site. It can -- presumably -- say no to his project in order to protect Boise, even if filling Donald's 2.5 acres of wetlands will do no damage whatever to waters of the United States. If Donald were to build his pad on dry land where he didn't need a Corps permit, then of course the Corps would not have regulatory control; the Corps would not be a player in Donald's scheme, and Donald could bomb Boise to his heart's content. But since the Corps is a player, it seems to me that it has to consider the impacts of Donald's plans, wherever they may occur.

And of course, the Corps does have regulatory control over Donald's proposed launch site. It can -- presumably -- say no to his project in order to protect Boise, even if filling Donald's 2.5 acres of wetlands will do no damage whatever to waters of the United States. If Donald were to build his pad on dry land where he didn't need a Corps permit, then of course the Corps would not have regulatory control; the Corps would not be a player in Donald's scheme, and Donald could bomb Boise to his heart's content. But since the Corps is a player, it seems to me that it has to consider the impacts of Donald's plans, wherever they may occur.

I think the confusion between “area of regulatory control” and “area(s) where environmental impacts may occur” that's reflected in the Sierra Club decision results from a misinterpretation of what the Sierra Club court referred to as "NEPA analysis" -- that is, the work that must be done to determine what a projects's environmental impacts may be and what to do about them. It is widely assumed that to perform such analysis, under the NEPA or under a more specific statute like the NHPA, the responsible federal agency must require that detailed studies be done in order to determine what effects will

occur – counting how many endangered owls live in the potentially affected area or how many ancestral

indigenous graves may lie hidden in its soil. Doing these things costs money,

and environmental consulting firms understandably assure agencies and regulated

industries that they must be done in order to assess effects. Those who

pay the bills for such work naturally seek relief, and the Corps has seized on its lack of “regulatory control” over areas of potential effect as the means of providing it.

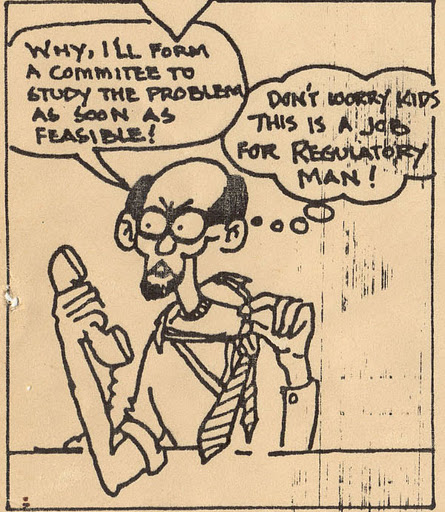

“You can’t

possibly require me to count endangered lizards and old buildings in Boise as a

condition of my permit in Florida!” Donald thunders, and the Corps quickly

moves to mollify him. “No sir, no sir, don’t you worry, sir. Boise isn’t even in our

Division; we don’t have any – er – regulatory control over what your project

does there.”

This is

obviously nuts. The Corps should certainly consider what giving Donald his

permit may do to Boise and its environment, and if it determines that the

public interest demands saving the city at the expense of Donald’s right to use

his Florida marshland as he sees fit, it should deny the permit. Exactly what processes the Corps may

need to employ in giving the matter such consideration, and what studies may be

necessary (if any) depend on the character of the case. In Donald's case, one doesn't need to find and evaluate every National Register eligible building in town to know that nuking them all will have adverse effects, or that other aspects of the city's environment (like the welfare of its resident lizards, owls, and human beings) will be drastically impacted.

Turning

to a real-life case, consider the Dakota Access Pipeline (http://www.daplpipelinefacts.com/),

a proposed almost 1200-mile oil pipeline between northwestern North Dakota and southern Illinois. Its construction will require the Corps to issue over 200

permits for water-crossings; without these crossings the project cannot be

built. Should the Corps look at the impacts of the whole project – as affected

Indian tribes and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, among others,

propose? Or should it spend its time on 200+ individual permit actions and

ignore the project’s overall effects? The Corps, I’m told – citing Sierra Club – says it can do only the

latter. This strikes me as no more justified – or consistent with the intent of

the NEPA and the NHPA – than letting Donald bomb Boise without first inquiring into the impacts of doing so. The Corps should stop playing semantic games with its regulatory language and sit down with the tribes and others concerned to determine how to address the project's overall potential effects.

[1]

Oddly enough, the city of Boise, Oklahoma (not Idaho) WAS bombed during World

War II; see http://hubpages.com/travel/BoiseCityBombing